True fantasy is hopeless. As the hero nears faery, faery recedes. Magic is always a

double-edged sword, and the price of using it is often to give it up. No one knows these tragic lineaments better than John Crowley, who has spent the greater part of his career on the border of faery, always showing us glimpses, never surrendering the key.

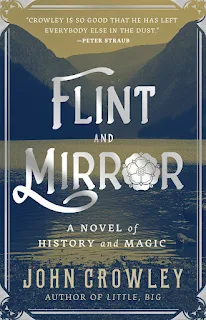

So it is with Flint and Stone, Crowley’s latest, a palimpsest of ancient magic on historical fact. It’s familiar territory for Crowley, Elizabethan England, the England of Elizabeth’s magician, John Dee, the age of magic diminishing and disappearing. But this tale is set mainly in Ireland, where they’ve always been closest to faery, and always closest to tragedy, and never more so than in the tale of Hugh, the earl of Tyrone, torn between his Irish heritage and English upbringing, and Red Hugh of Donegal, the prince who could unite the warring Irish under him—but never has the chance.

And here’s the fact of tragedy—we always know the outcome from the very beginning. We know (everyone knows this truth of Ireland—it has never been united to this day) that it ends in disappointment and death. This is what lifts the story of the earl of Tyrone, as indecisive as Hamlet, to catharsis. England loses as surely as Ireland does. England loses Elizabeth, and Ireland loses the magic that inhabits the hollow hills.

This is a special tale—in its simplicity, in its solidity, and in its intangibility. If you’ve never read any John Crowley, this is a good place to start. Highly recommended.